Guyana Tarihi - History of Guyana - Wikipedia

Bu makale için ek alıntılara ihtiyaç var doğrulama. (Aralık 2020) (Bu şablon mesajını nasıl ve ne zaman kaldıracağınızı öğrenin) |

Parçası bir dizi üzerinde | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tarihi Guyana | ||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

Guyana tarihi yaklaşık 35.000 yıl önce, Afro-Avrasya. Bu göçmenler Carib ve Arawak Alonso de Ojeda'nın İspanya'dan ilk seferiyle 1499'da tanışan kabileler, Essequibo Nehri. İzleyen sömürge döneminde, Guyana hükümeti İspanyol, Fransız, Hollandalı ve İngiliz yerleşimcilerin birbirini izleyen politikaları tarafından tanımlandı.

Sömürge döneminde Guyana'nın ekonomisi, başlangıçta köle emeğine bağlı olan plantasyon tarımına odaklanmıştı. Guyana, büyük köle isyanlarını gördü 1763 ve yine içinde 1823, ikincisi 1838'de bölgede köleliğin nihai olarak ortadan kaldırılmasına yol açtı. İşgücü sıkıntısını gidermek için, plantasyonlar Hindistan'dan düşük ücretli sözleşmeli işçilerle sözleşme yapmaya başladı. Sonunda, bu Kızılderililer, hükümette ve toplumda eşit haklar talep etmek için Afro-Guyanlı kölelerin torunları ile güçlerini birleştirdi. Ruimveldt İsyanları. Bu eşitlik mücadelesi sonunda özerkliğin artmasına ve nihayet 26 Mayıs 1966'da bağımsızlığa yol açtı.

Bağımsızlığın ardından, Forbes Burnham iktidara yükseldi, hızla sosyalizmi Guyana'ya getirme sözü veren otoriter bir lider haline geldi. Gücü, Guyana'ya getirilen uluslararası dikkatin ardından zayıflamaya başladı. Jonestown 1978'deki katliamlar. 1985'teki beklenmedik ölümünden sonra, iktidar barışçıl bir şekilde Desmond Hoyte 1992'de oylanmadan önce bazı demokratik reformları uygulayan.

Sömürge öncesi Guyana ve ilk temaslar

Guyana'ya ulaşan ilk insanlar, belki de 35.000 yıl önce, Asya'dan geldiler. Bu ilk sakinler göçebeler Yavaş yavaş güneye Orta ve Güney Amerika'ya göç etti. Zamanında Kristof Kolomb Guyana'nın sakinleri seferleri iki gruba ayrıldı: Arawak sahil boyunca ve Carib iç mekanda. Yerli halkların miraslarından biri, genellikle modern Guyana'yı ve aynı zamanda modern Guyana'yı kapsayan bölgeyi tanımlamak için kullanılan Guiana kelimesiydi. Surinam (eski Hollanda Guyanası) ve Fransız Guyanası. "Sular ülkesi" anlamına gelen kelime, bölgenin çok sayıdaki nehir ve akarsuları düşünüldüğünde uygundur.

Tarihçiler, Arawaks ve Caribs'ın Güney Amerika kökenli olduğunu düşünüyorlar. hinterland kuzeye, önce günümüz Guianas'ına ve sonra da Karayip Adaları. Ağırlıklı olarak yetiştiriciler, avcılar ve balıkçılar olan Arawak, Karayip adalarından önce Karayip adalarına göç etti ve bölgeye yerleşti. Arawak toplumunun sükuneti, Güney Amerika'nın iç kesimlerinden savaşan Carib'in gelişiyle bozuldu. Carib'in savaşçı davranışları ve kuzeye şiddetli göçü bir etki yarattı. 15. yüzyılın sonunda, Karayipler, Arawak'ı Kuzey Denizi adaları boyunca yerinden etti. Küçük Antiller. Küçük Antiller'in Carib yerleşimi de Guyana'nın gelecekteki gelişimini etkiledi. Kolomb'un peşinden gelen İspanyol kaşifler ve yerleşimciler, Arawak'ı fethetmenin bağımsızlıklarını korumak için çok mücadele eden Carib'den daha kolay olduğunu keşfettiler. Bu şiddetli direniş, Küçük Antiller'de altın eksikliği ile birlikte, İspanyolların fethi ve yerleşimi üzerindeki vurgusuna katkıda bulundu. Büyük Antiller ve anakara. İspanya'nın Küçük Antiller'deki otoritesini pekiştirmek için yalnızca zayıf bir İspanyol çabası gösterildi (tartışılabilir istisna hariç) Trinidad ) ve Guianas.

Sömürge-Guyana

Erken kolonizasyon

Flemenkçe günümüz Guyana'sına yerleşen ilk Avrupalılardı. Hollanda vardı İspanya'dan bağımsızlık elde etti 16. yüzyılın sonlarında ve 17. yüzyılın başlarında Küçük Antiller'deki yeni İngiliz ve Fransız kolonileriyle ticaret yaparak büyük bir ticari güç olarak ortaya çıktı. 1616'da Hollandalılar, Guyana bölgesinde, ağzının yirmi beş kilometre yukarısında bir ticaret noktası olan ilk Avrupa yerleşimini kurdu. Essequibo Nehri. Bunu genellikle birkaç kilometre içeride daha büyük nehirlerin üzerinde başka yerleşim yerleri izledi. Hollanda yerleşimlerinin ilk amacı yerli halkla ticaret yapmaktı. Diğer Avrupalı güçler Karayipler'in başka yerlerinde koloniler kazandıkça, Hollandalıların hedefi kısa sürede toprak elde etmeye dönüştü. Guyana, bölgeye periyodik devriye gönderen İspanyollar tarafından talep edilmesine rağmen, Hollandalılar 17. yüzyılın başlarında bölgenin kontrolünü ele geçirdiler. Hollanda egemenliği resmi olarak Munster Antlaşması 1648'de.

1621'de Hollanda hükümeti yeni kurulan Hollandalı Batı Hindistan Şirketi Essequibo'daki ticaret merkezi üzerinde tam kontrol. Bu Hollanda ticari kaygısı koloniyi yönetti. Essequibo 170 yılı aşkın süredir. Şirket, ikinci bir koloni kurdu. Berbice Nehri güneydoğusunda Essequibo, 1627'de. Bu özel grubun genel yetkisi altında olmasına rağmen, yerleşim, Berbice, ayrı yönetildi. Demerara Essequibo ve Berbice arasında yer alan, 1741'de yerleşti ve 1773'te Hollanda Batı Hindistan Şirketi'nin doğrudan kontrolü altında ayrı bir koloni olarak ortaya çıktı.

Hollandalı sömürgeciler başlangıçta Karayipler'deki ticaret beklentisiyle motive olmuş olsalar da, mülkleri önemli ürün üreticileri haline geldi. Tarımın artan önemi, 15.000 kg. tütün 1623'te Essequibo'dan. Ancak Hollanda kolonilerinin tarımsal üretkenliği arttıkça bir işgücü sıkıntısı ortaya çıktı. Yerli halk, üzerinde çalışmak için yetersiz bir şekilde uyarlanmıştı. tarlalar ve birçok insan öldü Avrupalıların getirdiği hastalıklar. Hollandalı Batı Hindistan Şirketi, köleleştirilmiş Afrikalılar, sömürge ekonomisinde hızla kilit bir unsur haline gelen. 1660'larda köleleştirilmiş nüfus yaklaşık 2.500'tü; Yerli halkın sayısının 50.000 olduğu tahmin ediliyordu ve bunların çoğu geniş hinterlandlara çekilmişti. Köleleştirilmiş Afrikalılar sömürge ekonomisinin temel bir unsuru olarak görülse de, çalışma koşulları acımasızdı. Ölüm oranı yüksekti ve iç karartıcı koşullar, köleleştirilmiş Afrikalıların önderliğinde yarım düzineden fazla isyana yol açtı.

Köleleştirilmiş Afrikalıların en ünlü ayaklanması, Berbice Köle Ayaklanması, Şubat 1763'te başladı. Canje Nehri Berbice'de köleleştirilmiş Afrikalılar isyan ederek bölgenin kontrolünü ele geçirdiler. Plantasyondan sonra plantasyon köleleştirilmiş Afrikalıların eline geçtiğinde, Avrupa nüfusu kaçtı; sonunda kolonide yaşayan beyazların sadece yarısı kaldı. Liderliğinde Coffy (şimdi Guyana'nın ulusal kahramanı), kaçan köleleştirilmiş Afrikalıların sayısı yaklaşık 3.000'e ulaştı ve Avrupa'nın Guianas üzerindeki kontrolünü tehdit etti. İsyancılar, İngilizler, Fransızlar gibi komşu Avrupa kolonilerinden gelen birliklerin yardımıyla yenildiler. Sint Eustatius ve denizaşırı Hollanda Cumhuriyeti. Guyana, Georgetown'daki Devrim Meydanı'ndaki 1763 Anıtı ayaklanmayı anıyor.

İngiliz yönetimine geçiş

Daha fazla yerleşimci çekmeye istekli olan Hollandalı yetkililer 1746'da Demerara Nehri İngiliz göçmenlere. Küçük Antiller'deki İngiliz plantasyon sahipleri fakir toprak ve erozyonla boğuşuyordu ve birçoğu daha zengin topraklar ve toprak sahibi olma vaadiyle Hollanda kolonilerine çekildi. İngiliz vatandaşlarının akını o kadar büyüktü ki, 1760'da İngilizler, Demerara'nın Avrupa nüfusunun çoğunluğunu oluşturuyordu.[kaynak belirtilmeli ] 1786'ya gelindiğinde, bu Hollanda kolonisinin iç işleri fiilen İngiliz kontrolü altındaydı.[kaynak belirtilmeli ] plantasyon sahiplerinin üçte ikisi hala Hollandalıydı.[1]

Demerara ve Essequibo'da ekonomik büyüme hızlandıkça, ekiciler ile Hollandalı Batı Hindistan Şirketi arasındaki ilişkilerde gerginlikler görülmeye başladı. 1770'lerin başındaki idari reformlar, hükümetin maliyetini büyük ölçüde artırmıştı. Şirket, bu harcamaları karşılamak için periyodik olarak vergileri artırmaya çalıştı ve böylelikle ekicilerin direncini kışkırttı. 1781 a savaş Berbice, Essequibo ve Demerara'nın İngiliz işgali ile sonuçlanan Hollanda ile İngiltere arasında patlak verdi. Birkaç ay sonra, Hollanda ile müttefik olan Fransa, kolonilerin kontrolünü ele geçirdi. Fransızlar, Demerara Nehri'nin ağzına yeni bir kasaba olan Longchamps'ı inşa ettikleri iki yıl boyunca hüküm sürdü. Hollandalılar 1784'te yeniden iktidara geldiğinde, sömürge başkentlerini Stabroek olarak yeniden adlandırdıkları Longchamps'a taşıdılar. Başkent 1812'de yeniden adlandırıldı Georgetown İngilizler tarafından.

Hollanda yönetiminin geri dönüşü, Essequibo ve Demerara ekicileriyle Hollanda Batı Hindistan Şirketi arasındaki çatışmayı yeniden alevlendirdi. Köle vergisinde bir artış ve koloninin yargı ve politika konseylerinde temsillerinin azaltılması planlarından rahatsız olan sömürgeciler, şikayetlerini dikkate almaları için Hollanda hükümetine dilekçe verdiler. Buna cevaben, özel bir komite atandı ve bu komite, Düzeltme Konsept Planı. Bu belge, geniş kapsamlı anayasa reformları çağrısında bulundu ve daha sonra İngiliz hükümet yapısının temeli oldu. Plan, bir karar alma organı önerdi. Politika Mahkemesi. Yargı, biri Demerara'ya, diğeri Essequibo'ya hizmet veren iki adalet mahkemesinden oluşacaktı. Politika Mahkemesi ve adalet mahkemelerinin üyelikleri şirket yetkilileri ve yirmi beşten fazla köleye sahip yetiştiricilerden oluşacaktı. Bu yeni hükümet sistemini uygulama sorumluluğunu üstlenen Hollanda komisyonu, Hollanda Batı Hindistan Şirketi'nin yönetimiyle ilgili son derece olumsuz raporlarla Hollanda'ya döndü. Bu nedenle şirketin tüzüğünün 1792'de sona ermesine izin verildi ve Düzeltme Konsept Planı Demerara ve Essequibo'da yürürlüğe girdi. Yeniden adlandırıldı Birleşik Demerara ve Essequibo Kolonisi, bölge daha sonra Hollanda hükümetinin doğrudan kontrolü altına girdi. Berbice, ayrı bir koloni olarak statüsünü sürdürdü.

Resmi İngilizlerin ele geçirilmesinin katalizörü, Fransız devrimi ve sonraki Napolyon Savaşları. 1795'te Fransızlar Hollanda'yı işgal etti. İngilizler Fransa'ya savaş ilan etti ve 1796'da Barbados Hollanda kolonilerini işgal etmek. İngilizlerin ele geçirilmesi kansızdı ve koloninin yerel Hollanda yönetimi, Düzeltme Konsept Planı tarafından sağlanan anayasa uyarınca nispeten kesintisiz kaldı.

Hem Berbice hem de Demerara ve Essequibo Birleşik Kolonisi 1796'dan 1802'ye kadar İngiliz kontrolü altındaydı. Amiens Antlaşması, ikisi de Hollanda kontrolüne iade edildi. Ancak barış kısa sürdü. İngiltere ile Fransa arasındaki savaş bir yıldan kısa bir süre içinde yeniden başladı ve 1803'te Birleşik Koloni ve Berbice bir kez daha İngiliz birlikleri tarafından ele geçirildi. Şurada 1814 Londra Sözleşmesi her iki koloni de resmi olarak Britanya'ya devredildi. 1831'de Berbice ve Birleşik Demerara ve Essequibo Kolonisi, İngiliz Guyanası. Koloni, 1966'daki bağımsızlığa kadar İngiliz kontrolü altında kalacaktı.

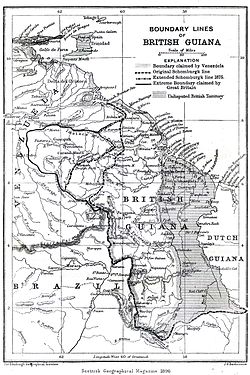

Venezuela ile sınır anlaşmazlığının kökenleri

Britanya, 1814'te şu anda Guyana olan üzerinde resmi kontrol elde ettiğinde, aynı zamanda Latin Amerika'nın en ısrarlı sınır anlaşmazlıklarından birine dahil oldu. 1814 Londra Konvansiyonu'nda Hollandalılar, Birleşik Demerara ve Essequibo ve Berbice Kolonisi'ni, Venezuela'nın İspanyol kolonisi ile batı sınırı Essequibo nehri olan İngiliz kolonisine teslim ettiler. İspanya hala bölgeyi talep etmesine rağmen, İspanyollar kendi kolonilerinin bağımsızlık mücadeleleriyle meşgul oldukları için anlaşmaya itiraz etmediler. 1835'te İngiliz hükümeti Alman kaşif Robert Hermann Schomburgk İngiliz Guyanası'nın haritasını çıkarmak ve sınırlarını belirlemek için. İngiliz makamlarının emriyle Schomburgk, İngiliz Guyanası'nın batı sınırına Venezuela ağzında Orinoco Nehri Ancak tüm Venezuela haritaları Essequibo nehrini ülkenin doğu sınırı olarak gösteriyordu. 1840 yılında İngiliz kolonisinin bir haritası yayınlandı. Venezuela, Essequibo Nehri'nin batısındaki tüm alanı talep ederek protesto etti. İngiltere ile Venezuela arasında sınır üzerine müzakereler başladı, ancak iki ülke uzlaşmaya varamadı. 1850'de her ikisi de tartışmalı bölgeyi işgal etmemeyi kabul etti.

1850'lerin sonlarında ihtilaflı bölgede altının keşfi, tartışmayı yeniden alevlendirdi. İngiliz yerleşimciler bölgeye taşındı ve İngiliz Guyanası Madencilik Şirketi yatakları çıkarmak için oluşturuldu. Yıllar geçtikçe Venezuela defalarca protestolar yaptı ve tahkim teklifinde bulundu, ancak İngiliz hükümeti ilgisizdi. Venezuela nihayet 1887'de İngiltere ile diplomatik ilişkilerini kesti ve yardım için Amerika Birleşik Devletleri'ne başvurdu. İngilizler ilk başta Amerika Birleşik Devletleri hükümetinin tahkim önerisini reddetti, ancak Başkan Grover Cleveland göre müdahale etmekle tehdit etti Monroe doktrini İngiltere, 1897'de uluslararası bir mahkemenin sınırı tahkim etmesine izin vermeyi kabul etti.

İki İngiliz, iki Amerikalı ve bir Rustan oluşan mahkeme iki yıl boyunca Paris'teki (Fransa) davayı inceledi.[2] 1899'da verilen üçe ikiye karar verdikleri bu karar, tartışmalı bölgenin yüzde 94'ünü İngiliz Guyanası'na verdi. Venezuela sadece Orinoco Nehri'nin ağızlarını ve hemen doğudaki Atlantik kıyı şeridinin kısa bir bölümünü aldı. Venezuela karardan memnun olmasa da, bir komisyon karar uyarınca yeni bir sınır araştırması yaptı ve her iki taraf da 1905'te sınırı kabul etti. Sorun önümüzdeki yarım yüzyıl için çözülmüş olarak kabul edildi.

Erken İngiliz Kolonisi ve işçi sorunu

19. yüzyılda politik, ekonomik ve sosyal yaşam, bir Avrupa ekici sınıfının hakimiyetindeydi. Rakam olarak en küçük grup olmasına rağmen, çiftçilerin idaresi Londra'daki İngiliz ticari çıkarlarıyla bağlantıları vardı ve hükümdar tarafından atanan valiyle sık sık yakın bağları vardı. Plantokrasi aynı zamanda ihracatı ve nüfusun çoğunluğunun çalışma koşullarını da kontrol ediyordu. Bir sonraki sosyal katman, az sayıda özgürleştirilmiş köleler, bazılarına ek olarak birçok karışık Afrika ve Avrupa mirası Portekizce tüccarlar. Toplumun en alt düzeyinde, tarlaların bulunduğu kırsalda yaşayan ve çalışan Afrikalı köleler çoğunluktu. İç bölgelerde kolonyal yaşamla bağlantısı olmayan küçük Amerikalı gruplar yaşıyordu.

Köleliğin sona ermesiyle sömürge hayatı kökten değişti. Uluslararası köle ticareti olmasına rağmen kaldırıldı içinde ingiliz imparatorluğu 1807'de köleliğin kendisi devam etti. Olarak bilinen şeyde 1823 Demerara isyanı 10-13.000 köle Demerara-Essequibo zalimlerine karşı ayaklandı.[3] İsyan kolayca bastırılsa da,[3] yürürlükten kaldırılma ivmesi devam etti ve 1838'de tam bir özgürleşme gerçekleşti. Köleliğin sona ermesinin birkaç sonucu vardı. En önemlisi, birçok eski köle tarlalardan hızla ayrıldı. Bazı eski köleler, tarla işçiliğinin aşağılayıcı ve özgürlükle tutarsız olduğunu düşünerek kasaba ve köylere taşındı, ancak diğerleri kaynaklarını eski efendilerinin terk edilmiş mülklerini satın almak için birleştirdi ve köy toplulukları yarattı. Küçük yerleşim yerleri kurmak, yeni Afro-Guyanlı topluluklara yiyecek yetiştirme ve satma fırsatı sağladı; bu, kölelerin herhangi bir fazla ürünün satışından elde edilen parayı elinde tutmasına izin verilen bir uygulamanın bir uzantısı oldu. Bununla birlikte, bağımsız fikirli bir Afro-Guyanlı köylü sınıfının ortaya çıkışı, ekiciler artık koloninin ekonomik faaliyeti üzerinde neredeyse tekele sahip olmadıkları için, yetiştiricilerin siyasi gücünü tehdit etti.

Kurtuluş ayrıca yeni etnik ve kültürel grupların İngiliz Guyanası'na girmesiyle sonuçlandı. Afro-Guyanlıların şeker plantasyonlarından ayrılması kısa sürede işçi kıtlığına yol açtı. 19. yüzyıl boyunca Portekizli işçileri çekmek için yapılan başarısız girişimlerin ardından Madeira, mülk sahiplerine yine yetersiz işgücü arzı kaldı. Portekizliler plantasyon işine girmemişlerdi ve kısa bir süre sonra ekonominin diğer kısımlarına, özellikle perakende ticaretine geçtiler ve burada yeni Afro-Guyanlı orta sınıfla rakip haline geldiler. 1853 ile 1912 arasında koloniye 14.000 kadar Çinli geldi. Portekizli selefleri gibi Çinliler de perakende ticaret için plantasyonları terk ettiler ve kısa süre sonra Guianese toplumunda asimile oldular.

Plantasyonların daralan iş gücü havuzu ve potansiyel düşüşle ilgili endişeler. şeker sektör, İngiliz yetkililer, Hollanda Guyanası'ndaki meslektaşları gibi, düşük ücretli hizmetler için sözleşme yapmaya başladılar. Hindistan'dan sözleşmeli işçiler. Bu grubun yerel olarak bilindiği şekliyle Doğu Kızılderilileri, belirli bir süre için anlaşma imzaladılar, ardından teoride şeker tarlalarında çalışmaktan elde ettikleri birikimle Hindistan'a döneceklerdi. Sözleşmeli Doğu Hindistanlı işçilerin devreye girmesi, işgücü açığını azalttı ve Guyana'nın etnik karışımına başka bir grup ekledi. Doğu Hindistanlı işçilerin çoğunluğunun kökenleri doğu Uttar Pradesh'e dayanıyordu, daha küçük bir kısmı ise güney Hindistan'daki Tamil ve Telugu konuşulan bölgelerden geliyordu. Bu işçilerin küçük bir azınlığı Bengal, Pencap ve Gujarat gibi diğer bölgelerden geldi. Hindistan'ın İngiliz işgali altındaki bölgeleri, on yıllardır neden olduğu kıtlıklar nedeniyle harap olmuştu. İngiliz politikaları göç etmeye istekli işçilerin geniş bir şekilde bulunmasına yol açar.

Siyasi ve sosyal uyanışlar

On dokuzuncu yüzyıl İngiliz Guyanası

İngiliz kolonisinin anayasası, beyaz ve Güney Asyalı yetiştiricileri destekliyordu. Planter'ın siyasi gücü, 18. yüzyılın sonlarında Hollanda yönetimi altında kurulan Politika Mahkemesi ve iki adalet mahkemesine dayanıyordu. Politika Mahkemesi hem yasama hem de idari işlevlere sahipti ve valinin başkanlığında vali, üç sömürge memuru ve dört sömürgeciden oluşuyordu. Adalet mahkemeleri, dilekçe ile önlerine getirilen ruhsatlandırma ve kamu hizmeti atamaları gibi adli konuları çözdü.

Plantasyon sahipleri tarafından kontrol edilen Politika Mahkemesi ve adalet mahkemeleri, İngiliz Guyanası'ndaki gücün merkezini oluşturdu. Politika Mahkemesi ve adalet mahkemelerinde oturan sömürgeciler, vali tarafından iki seçim kolejinin sunduğu adaylar listesinden atandı. Sırayla, her birinin yedi üyesi Seçmenler Koleji yirmi beş veya daha fazla köleye sahip olan yetiştiriciler tarafından ömür boyu seçildi. Güçleri, üç büyük hükümet konseyindeki boş yerleri doldurmaları için sömürgecileri aday göstermekle sınırlı olsa da, bu seçim kolejleri ekiciler tarafından siyasi ajitasyon için bir ortam sağladı.

Geliri artırmak ve kullanmak, Kombine Mahkeme Politika Mahkemesi üyeleri ve Seçmenler Koleji tarafından atanan altı ek mali temsilci içeren. 1855'te Birleşik Mahkeme ayrıca tüm hükümet görevlilerinin maaşlarını belirleme sorumluluğunu da üstlendi. Bu görev Birleşik Mahkeme'yi bir entrika merkezi haline getirdi ve bu da vali ile tarla sahipleri arasında periyodik çatışmalara neden oldu.

Diğer Guyanlılar 19. yüzyılda daha temsili bir siyasi sistem talep etmeye başladı. 1880'lerin sonlarına doğru, yeni Afro-Guyanlı orta sınıfın baskısı anayasal reform için inşa ediliyordu. Özellikle, Politika Mahkemesini on seçilmiş üyeli bir meclise dönüştürmek, seçmen niteliklerini kolaylaştırmak ve Seçmenler Koleji'ni kaldırmak için çağrılar yapıldı. Reformlar, liderliğindeki yetiştiriciler tarafından direndi. Henry K. Davson, büyük bir plantasyonun sahibi. Londra'da yetiştiricilerin müttefikleri vardı Batı Hindistan Komitesi ve ayrıca Glasgow Batı Hindistan Derneği her ikisi de İngiliz Guyanası'nda büyük çıkarları olan mülk sahiplerinin başkanlığını yaptı.

1891'deki anayasal revizyonlar, reformcuların talep ettiği bazı değişiklikleri içeriyordu. Yetiştiriciler, Seçmen Koleji'nin kaldırılması ve seçmen kalifikasyonunun gevşetilmesi ile siyasi nüfuzunu kaybetti. Aynı zamanda, Politika Mahkemesi on altı üyeye genişletildi; bunlardan sekizi, yetkileri atanmış sekiz üye ile dengelenecek olan seçilmiş üyeler olacaktı. Birleşik Mahkeme, daha önce olduğu gibi, Politika Mahkemesi ve şu anda seçilmiş olan altı mali temsilciden oluşan mahkemeye de devam etti. Vali, seçilmiş görevlilere herhangi bir iktidar kayması olmamasını sağlamak için, Politika Mahkemesinin başı olarak kaldı; Politika Mahkemesinin yürütme görevleri yeni bir Yürütme Kurulu vali ve yetiştiricilerin hakim olduğu. 1891 revizyonları, koloninin reformcuları için büyük bir hayal kırıklığı oldu. Sonuç olarak 1892 seçimleri, yeni Birleşik Mahkeme üyeliği bir öncekiyle hemen hemen aynıydı.

Önümüzdeki otuz yıl, küçük de olsa ek politik değişiklikler gördü. 1897'de gizli oy tanıtılmıştı. 1909'da yapılan bir reform, sınırlı İngiliz Guyanası seçmenlerini genişletti ve ilk kez Afro-Guyanlı seçmenlerin çoğunluğunu oluşturdu.

Siyasi değişikliklere, artan güç için çeşitli etnik gruplar tarafından sosyal değişim ve jokey eşlik etti. İngiliz ve Hollandalı yetiştiriciler Portekizlileri eşit olarak kabul etmeyi reddettiler ve kolonide hiçbir hakkı, özellikle de oy hakkı olmayan yabancılar statüsünü korumaya çalıştılar. Siyasi gerilimler Portekizlilerin Reform Derneği. Sonra 1898 Portekiz karşıtı isyanlar Portekizliler Guyan toplumunun haklarından mahrum edilmiş diğer unsurlarla, özellikle Afro-Guyanlılarla çalışma ihtiyacını kabul etti. 20. yüzyılın başlarında, Reform Derneği ve Reform Kulübü koloninin işlerine daha fazla katılım talep etmeye başladı. Bu örgütler, büyük ölçüde, küçük ama kendini belli eden bir orta sınıfın araçlarıydı. Yeni orta sınıf işçi sınıfına sempati duysa da, orta sınıf siyasi gruplar ulusal bir siyasi veya sosyal hareketi pek temsil etmiyorlardı. Nitekim, işçi sınıfının şikayetleri genellikle isyan şeklinde ifade ediliyordu.

Yirminci yüzyılın başlarında siyasi ve sosyal değişiklikler

1905 Ruimveldt İsyanları İngiliz Guyanası salladı. Bu patlamaların ciddiyeti, işçilerin yaşam standartları konusundaki yaygın memnuniyetsizliğini yansıtıyordu. Ayaklanma, Georgetown'un stevedores daha yüksek ücret talep ederek greve gitti. Grev çatışmacı bir şekilde büyüdü ve diğer işçiler sempati duyarak ülkenin ilk kent-kır işçi ittifakını yarattı. 30 Kasım'da, kalabalıklar Georgetown sokaklarına çıktı ve şimdi Kara Cuma olarak anılan 1 Aralık 1905'te durum kontrolden çıktı. Şurada Plantasyon Ruimveldt Georgetown yakınlarında, büyük bir hamal kalabalığı, bir polis devriyesi ve bir topçu müfrezesi tarafından emredildiğinde dağılmayı reddetti. Sömürge yetkilileri ateş açtı ve dört işçi ağır yaralandı.

Çatışmaların haberi Georgetown'da hızla yayıldı ve düşman kalabalıklar şehirde dolaşarak bir dizi binayı ele geçirmeye başladı. Günün sonunda yedi kişi öldü ve on yedi kişi ağır yaralandı. İngiliz yönetimi panik içinde yardım istedi. Britanya, sonunda ayaklanmayı bastıran birlikler gönderdi. Atılganların grevi başarısızlıkla sonuçlansa da, isyanlar, örgütlü bir sendikal hareket haline gelecek şeyin tohumlarını atmıştı.

Buna rağmen birinci Dünya Savaşı Britanya Guyanası sınırlarının çok ötesinde savaşıldı, savaş Guyan toplumunu değiştirdi. İngiliz ordusuna katılan Afro-Guyanlılar, geri döndüklerinde elit bir Afro-Guyan topluluğunun çekirdeği haline geldi. Birinci Dünya Savaşı, Doğu Hindistan sözleşmeli hizmetinin de sona ermesine yol açtı. İngilizlerin Hindistan'daki siyasi istikrar konusundaki endişeleri ve Hintli milliyetçilerin programın bir tür insan esareti olduğu yönündeki eleştirileri, İngiliz hükümetinin 1917'de sözleşmeli işçiliği yasadışı ilan etmesine neden oldu.

Birinci Dünya Savaşı'nın son yıllarında, koloninin ilk sendikası kuruldu. İngiliz Guyanası İşçi Sendikası (BGLU), 1917 yılında H.N. Critchlow ve liderliğinde Alfred A. Thorne. Yaygın iş muhalefeti karşısında kurulan BGLU, ilk başta en çok Afro-Guyanlıyı temsil etti. liman işçileri. Üyeliği 1920'de 13.000 civarındaydı ve 1921'de Esnaf Birliği Yönetmeliği. Diğer sendikaların tanınması 1939'a kadar gelmese de BGLU, işçi sınıfının siyasi olarak bilinçlendiğinin ve haklarıyla daha çok ilgilenmeye başladığının bir göstergesiydi.

İkinci sendika, İngiliz Guyanası İşçi Birliği, 1931'de Alfred A. Thorne 22 yıldır Lig lideri olarak görev yapan. Birlik, kolonideki tüm etnik kökenden insanlar için çalışma koşullarını iyileştirmeye çalıştı. İşçilerin çoğu Batı Afrika, Doğu Hindistan, Çin ve Portekiz kökenliydi ve ülkeye zorunlu veya sözleşmeli çalıştırma sistemi altında getirilmişlerdi.

Birinci Dünya Savaşı'ndan sonra, Birleşik Mahkeme ile yeni ekonomik çıkar grupları çatışmaya başladı. Ülkenin ekonomisi şekere daha az, pirince ve boksit ve bu yeni malların üreticileri, şeker ekicilerinin Birleşik Saray'daki hâkimiyetini sürdürmesine kızdı. Bu arada, ekiciler düşük şeker fiyatlarının etkilerini hissediyorlardı ve Birleşik Mahkeme'den yeni drenaj ve sulama programları için gerekli fonları sağlamasını istiyorlardı.

Tartışmayı ve bunun sonucunda ortaya çıkan yasama felçini durdurmak için, 1928'de Koloni Ofisi İngiliz Guyanası yapacak yeni bir anayasa ilan etti taç kolonisi Sömürge Dairesi tarafından atanan bir valinin sıkı kontrolü altında. Birleşik Mahkeme ve Politika Mahkemesi, bir Yasama meclisi atanan üyelerin çoğunluğuyla. Orta sınıf ve işçi sınıfı siyasi aktivistleri için bu yeni anayasa, bir geri adım ve ekiciler için bir zafer anlamına geliyordu. Belirli bir kamu politikasının teşvik edilmesinden ziyade vali üzerindeki etki, herhangi bir siyasi kampanyada en önemli konu haline geldi.

Büyük çöküntü 1930'ların, Guyan toplumunun tüm kesimlerine ekonomik zorluklar getirdi. Koloninin tüm büyük ihracatı - şeker, pirinç ve boksit - düşük fiyatlardan etkilendi ve işsizlik arttı. Geçmişte olduğu gibi, işçi sınıfı ekonomik koşulların kötüleştiği bir dönemde siyasi bir sesten yoksun buldu. 1930'ların ortalarında, Britanya Guyanası ve tüm Britanya Karayipleri, işçi isyanları ve şiddetli gösterilerle işaretlendi. Baştan sona ayaklanmaların ardından Britanya Batı Hint Adaları altında bir kraliyet komisyonu Lord Moyne isyanların nedenlerini belirlemek ve tavsiyelerde bulunmak amacıyla kurulmuştur.

İngiliz Guyanası'nda Moyne Komisyonu sendikacılar, Afro-Guyanlı profesyoneller ve Hint-Guyanalı toplum temsilcileri de dahil olmak üzere çok sayıda insanı sorguladı. Komisyon, ülkenin en büyük iki etnik grubu olan Afro-Guyanalı ve Hint-Guyanlı arasındaki derin bölünmeye dikkat çekti. En büyük grup olan Hint-Guyanlılar, öncelikle kırsal pirinç üreticileri veya tüccarlarından oluşuyordu; ülkenin geleneksel kültürünü korumuşlardı ve ulusal siyasete katılmamışlardı. Afro-Guyanlılar büyük ölçüde şehirli işçiler ya da boksit madencileriydi; Avrupa kültürünü benimsemiş ve ulusal siyasete hâkim olmuşlardı. Moyne Komisyonu, Britanya Guyanası'nda nüfusun çoğunluğunun temsilini artırmak için hükümetin demokratikleşmesinin yanı sıra ekonomik ve sosyal reformların artırılması çağrısında bulundu.

Moyne Komisyonu'nun 1938'deki raporu, İngiliz Guyanası için bir dönüm noktasıydı. İmtiyazın kadınlara ve toprak sahibi olmayan kişilere genişletilmesi çağrısında bulundu ve ortaya çıkan sendikal hareketi teşvik etti. Bununla birlikte, Moyne Komisyonu'nun tavsiyelerinin çoğu, salgını nedeniyle hemen uygulanmadı. Dünya Savaşı II ve İngiliz muhalefeti yüzünden.

Uzak çatışmalarla, İngiliz Guyanası'ndaki II.Dünya Savaşı dönemi, devam eden siyasi reformlar ve ulusal altyapıda yapılan iyileştirmelerle işaretlendi. Vali, efendim Gordon Lethem, ülkenin ilk On Yıllık Kalkınma Planını oluşturdu (Valinin Ekonomi Danışmanı Sir Oscar Spencer önderliğinde ve Alfred P. Thorne, Ekonomi Danışmanı Asistanı), ofis tutma ve oy kullanma için mülkiyet niteliklerini azalttı ve seçmeli üyeleri 1943'te Yasama Konseyinde çoğunluk yaptı. 1941 Borç Verme-Kiralama Yasası, modern bir hava üssü (şimdi Timehri Havaalanı ) Amerika Birleşik Devletleri birlikleri tarafından inşa edildi. II.Dünya Savaşı'nın sonunda, İngiliz Guyanası'nın siyasi sistemi, toplumun daha fazla unsurunu kapsayacak şekilde genişletildi ve ekonominin temelleri, artan boksit talebiyle güçlendirildi.

Bağımsızlık öncesi hükümet

Siyasi partilerin gelişimi

II.Dünya Savaşı'nın sonunda, toplumun her kesiminde siyasi farkındalık ve bağımsızlık talepleri arttı. Savaş sonrası dönem, Guyana'nın önde gelen siyasi partilerinin kuruluşuna tanık oldu. Halkın İlerici Partisi (PPP) 1 Ocak 1950'de kuruldu. PPP'de iç çatışmalar gelişti ve 1957'de Ulusal Halk Kongresi (PNC) bir bölünme olarak oluşturuldu. Bu yıllar aynı zamanda ülkenin iki baskın siyasi kişiliği arasında uzun ve acımasız bir mücadelenin başlangıcını gördü.Cheddi Jagan ve Linden Forbes Burnham.

Cheddi Jagan

Cheddi Jagan 1918'de Guyana'da doğdu. Ailesi Hindistan'dan göçmendi. Guyan toplumunun orta tabakasının en alt basamağında olduğu düşünülen bir pozisyon olan babası bir sürücüydü. Jagan'ın çocukluğu ona kırsal yoksulluk hakkında kalıcı bir fikir verdi. Zayıf geçmişlerine rağmen kıdemli Jagan oğlunu Kraliçe Koleji Georgetown'da. Oradaki eğitiminin ardından Jagan, diş hekimliği okumak için Amerika Birleşik Devletleri'ne gitti. kuzeybatı Üniversitesi içinde Evanston, Illinois 1942'de.

Jagan, Ekim 1943'te İngiliz Guyanası'na döndü ve kısa süre sonra eski Amerikalı karısı da katıldı. Janet Rosenberg, yeni ülkesinin siyasi gelişiminde önemli bir rol oynayacaktı. Jagan kendi diş hekimliği kliniğini kurmasına rağmen, kısa sürede siyasete karıştı. Guyana'nın siyasi hayatına bir dizi başarısız girişin ardından Jagan, İnsan Gücü Vatandaşları Derneği (MPCA) 1945'te. MPCA, koloninin çoğu Hint-Guyanlı olan şeker işçilerini temsil ediyordu. Jagan'ın görev süresi kısaydı çünkü politika meseleleri konusunda daha ılımlı sendika liderleriyle defalarca çatışıyordu. Katıldıktan bir yıl sonra MPCA'dan ayrılmasına rağmen, pozisyon Jagan'ın İngiliz Guyanası ve İngilizce konuşan Karayipler'deki diğer sendika liderleriyle görüşmesine izin verdi.

Linden Forbes Sampson Burnham

1923 doğumlu, Forbes Burnham üç çocuklu bir ailenin tek oğluydu. Babası okulun müdürüydü Kitty Methodist İlköğretim Okulu Georgetown'un hemen dışında bulunan. Koloninin eğitimli sınıfının bir parçası olarak genç Burnham, erken yaşta politik bakış açılarına maruz kaldı. Okulda son derece başarılı oldu ve hukuk derecesi almak için Londra'ya gitti. Jagan gibi çocukluk çağı yoksulluğuna maruz kalmasa da, Burnham ırk ayrımcılığının son derece farkındaydı.

1930'ların ve 1940'ların kentsel Afro-Guyan toplumunun sosyal katmanları melez veya "renkli" bir elit, siyah profesyonel bir orta sınıf ve en altta siyah işçi sınıfını içeriyordu. 1930'larda işsizlik yüksekti. When war broke out in 1939, many Afro-Guyanese joined the military, hoping to gain new job skills and escape poverty. When they returned home from the war, however, jobs were still scarce and discrimination was still a part of life.

Founding of the PAC and PPP

The springboard for Jagan's political career was the Political Affairs Committee (PAC), formed in 1946 as a discussion group. The new organization published the PAC Bulletin to promote its Marksist ideology and ideas of liberation and decolonization. The PAC's outspoken criticism of the colony's poor living standards attracted followers as well as detractors.

In the November 1947 general elections, the PAC put forward several members as independent candidates. The PAC's major competitor was the newly formed İngiliz Guyanası İşçi Partisi, which, under J.B. Singh, won six of fourteen seats contested. Jagan won a seat and briefly joined the Labour Party. But he had difficulties with his new party's center-right ideology and soon left its ranks. The Labour Party's support of the policies of the British governor and its inability to create a grass-roots base gradually stripped it of liberal supporters throughout the country. The Labour Party's lack of a clear-cut reform agenda left a vacuum, which Jagan rapidly moved to fill. Turmoil on the colony's sugar plantations gave him an opportunity to achieve national standing. After the June 16, 1948 police shootings of five Indo-Guyanese workers at Enmore, close to Georgetown, the PAC and the Guiana Industrial Workers' Union (GIWU) organized a large and peaceful demonstration, which clearly enhanced Jagan's standing with the Indo-Guyanese population.

After the PAC, Jagan's next major step was the founding of the Halkın İlerici Partisi (PPP) in January 1950. Using the PAC as a foundation, Jagan created from it a new party that drew support from both the Afro-Guyanese and Indo-Guyanese communities. To increase support among the Afro-Guyanese, Forbes Burnham was brought into the party.

The PPP's initial leadership was multi-ethnic and left of center, but hardly revolutionary. Jagan became the leader of the PPP's parliamentary group, and Burnham assumed the responsibilities of party chairman. Other key party members included Janet Jagan, Brindley Benn[4] ve Ashton Chase, both PAC veterans. The new party's first victory came in the 1950 municipal elections, in which Janet Jagan won a seat. Cheddi Jagan and Burnham failed to win seats, but Burnham's campaign made a favorable impression on many Afro-Guyanese citizens.

From its first victory in the 1950 municipal election, the PPP gathered momentum. However, the party's often strident antikapitalist ve sosyalist message made the British government uneasy. Colonial officials showed their displeasure with the PPP in 1952 when, on a regional tour, the Jagans were designated prohibited immigrants in Trinidad ve Grenada.

A British commission in 1950 recommended universal adult suffrage and the adoption of a bakanlık sistemi for British Guiana. The commission also recommended that power be concentrated in the Yönetim Bölümü, that is, the office of the governor. These reforms presented British Guiana's parties with an opportunity to participate in national elections and form a government, but maintained power in the hands of the British-appointed chief executive. This arrangement rankled the PPP, which saw it as an attempt to curtail the party's political power.

The first PPP government

Once the new constitution was adopted, elections were set for 1953. The PPP's coalition of lower-class Afro-Guyanese and rural Indo-Guyanese workers, together with elements of both ethnic groups' middle sectors, made for a formidable constituency. Conservatives branded the PPP as komünist, but the party campaigned on a center-left platform and appealed to a growing nationalism. The other major party participating in the election, the Ulusal Demokrat Parti (NDP), was a spin-off of the League of Coloured Peoples and was largely an Afro-Guyanese middle-class organization, sprinkled with middle-class Portuguese and Indo-Guyanese. The NDP, together with the poorly organized United Farmers and Workers Party ve Birleşik Ulusal Parti, was soundly defeated by the PPP. Final results gave the PPP eighteen of twenty-four seats compared with the NDP's two seats and four seats for independents.

The PPP's first administration was brief. The legislature opened on May 30, 1953. Already suspicious of Jagan and the PPP's radicalism, conservative forces in the business community were further distressed by the new administration's program of expanding the role of the state in the economy and society. The PPP also sought to implement its reform program at a rapid pace, which brought the party into confrontation with the governor and with high-ranking civil servants who preferred more gradual change. The issue of civil service appointments also threatened the PPP, in this case from within. Following the 1953 victory, these appointments became an issue between the predominantly Indo-Guyanese supporters of Jagan and the largely Afro-Guyanese backers of Burnham. Burnham threatened to split the party if he were not made sole leader of the PPP. A compromise was reached by which members of what had become Burnham's faction received ministerial appointments.

The PPP's introduction of the Labour Relations Act provoked a confrontation with the British. This law ostensibly was aimed at reducing intraunion rivalries, but would have favored the GIWU, which was closely aligned with the ruling party. The opposition charged that the PPP was seeking to gain control over the colony's economic and social life and was moving to stifle the opposition. The day the act was introduced to the legislature, the GIWU went on strike in support of the proposed law. The British government interpreted this intermingling of party politics and labor unionism as a direct challenge to the constitution and the authority of the governor. The day after the act was passed, on October 9, 1953, London suspended the colony's constitution and, under pretext of quelling disturbances, sent in troops.

The interim government

Following the suspension of the constitution, British Guiana was governed by an interim administration consisting of a small group of conservative politicians, businessmen, and civil servants that lasted until 1957. Order in the colonial government masked a growing rift in the country's main political party as the personal conflict between the PPP's Jagan and Burnham widened into a bitter dispute. In 1955 Jagan and Burnham formed rival wings of the PPP. Support for each leader was largely, but not totally, along ethnic lines. J. P. Lachmansingh, a leading Indo-Guyanese and head of the GIWU, supported Burnham, whereas Jagan retained the loyalty of a number of leading Afro-Guyanese radicals, such as Sidney Kralı. Burnham's wing of the PPP moved to the right, leaving Jagan's wing on the left, where he was regarded with considerable apprehension by Western governments and the colony's conservative business groups.

The second PPP government

1957 seçimleri held under a yeni anayasa demonstrated the extent of the growing ethnic division within the Guyanese electorate. The revised constitution provided limited özyönetim, primarily through the Legislative Council. Of the council's twenty-four delegates, fifteen were elected, six were nominated, and the remaining three were to be resen members from the interim administration. The two wings of the PPP launched vigorous campaigns, each attempting to prove that it was the legitimate heir to the original party. Despite denials of such motivation, both factions made a strong appeal to their respective ethnic constituencies.

The 1957 elections were convincingly won by Jagan 's PPP hizip. Although his group had a secure parliamentary majority, its support was drawn more and more from the Indo-Guyanese topluluk. The faction's main planks were increasingly identified as Indo-Guyanese: more rice land, improved union representation in the sugar industry, and improved business opportunities and more government posts for Indo-Guyanese.

Jagan's veto of İngiliz Guyanası katılımı Batı Hint Adaları Federasyonu resulted in the complete loss of Afro-Guyanalı destek. In the late 1950s, the British Caribbean colonies had been actively negotiating establishment of a West Indies Federation. The PPP had pledged to work for the eventual political union of British Guiana with the Caribbean territories. The Indo-Guyanese, who constituted a majority in Guyana, were apprehensive of becoming part of a federation in which they would be outnumbered by people of African descent. Jagan's veto of the federation caused his party to lose all significant Afro-Guyanese support.

Burnham learned an important lesson from the 1957 elections. He could not win if supported only by the lower-class, urban Afro-Guyanese. He needed orta sınıf allies, especially those Afro-Guyanese who backed the moderate Birleşik Demokrat Parti. From 1957 onward, Burnham worked to create a balance between maintaining the backing of the more radical Afro-Guyanese lower classes and gaining the support of the more capitalist middle class. Clearly, Burnham's stated preference for sosyalizm would not bind those two groups together against Jagan, an avowed Marksist. The answer was something more basic: yarış. Burnham's appeals to race proved highly successful in bridging the schism that divided the Afro-Guyanese along class lines. This strategy convinced the powerful Afro-Guyanese middle class to accept a leader who was more of a radical than they would have preferred to support. At the same time, it neutralized the objections of the black working class to entering an alliance with those representing the more moderate interests of the middle classes. Burnham's move toward the right was accomplished with the merger of his PPP faction and the United Democratic Party into a new organization, the Ulusal Halk Kongresi (PNC).

Following the 1957 elections, Jagan rapidly consolidated his hold on the Indo-Guyanese community. Though candid in expressing his admiration for Joseph Stalin, Mao Zedong, ve sonra, Fidel Castro Ruz, Jagan in power asserted that the PPP's Marxist-Leninist principles must be adapted to Guyana's own particular circumstances. Jagan advocated millileştirme of foreign holdings, especially in the sugar industry. British fears of a communist takeover, however, caused the British governor to hold Jagan's more radical policy initiatives in check.

PPP re-election and debacle

The 1961 elections were a bitter contest between the PPP, the PNC, and the United Force (UF), a conservative party representing big business, the Roma Katolik Kilisesi, and Amerindian, Chinese, and Portuguese voters. These elections were held under yet another new constitution that marked a return to the degree of self-government that existed briefly in 1953. It introduced a iki meclisli system boasting a wholly elected thirty-five-member Legislative Assembly and a thirteen-member Senate to be appointed by the governor. The post of prime minister was created and was to be filled by the majority party in the Legislative Assembly. With the strong support of the Indo-Guyanese population, the PPP again won by a substantial margin, gaining twenty seats in the Legislative Assembly, compared to eleven seats for the PNC and four for the UF. Jagan was named prime minister.

Jagan's administration became increasingly friendly with communist and leftist regimes; for instance, Jagan refused to observe the United States embargo on communist Küba. After discussions between Jagan and Cuban revolutionary Ernesto "Che" Guevara in 1960 and 1961, Cuba offered British Guiana loans and equipment. In addition, the Jagan administration signed trade agreements with Macaristan ve Alman Demokratik Cumhuriyeti (East Germany).

From 1961 to 1964, Jagan was confronted with a destabilization campaign conducted by the PNC and UF. In addition to domestic opponents of Jagan, an important role was played by the American Institute for Free Labor Development (AIFLD), which was alleged to be a front for the CIA. Various reports say that AIFLD, with a budget of US$800,000, maintained anti-Jagan labor leaders on its payroll, as well as an AIFLD-trained staff of 11 activists who were assigned to organize riots and destabilize the Jagan government. Riots and demonstrations against the PPP administration were frequent, and during disturbances in 1962 and 1963 mobs destroyed part of Georgetown, doing $40 million in damage.[5][6]

To counter the MPCA with its link to Burnham, the PPP formed the Guyana Tarım İşçileri Sendikası. This new union's political mandate was to organize the Indo-Guyanese sugarcane field-workers. The MPCA immediately responded with a one-day strike to emphasize its continued control over the sugar workers.

The PPP government responded to the strike in March 1964 by publishing a new Labour Relations Bill almost identical to the 1953 legislation that had resulted in British intervention. Regarded as a power play for control over a key labor sector, introduction of the proposed law prompted protests and rallies throughout the capital. Riots broke out on April 5; they were followed on April 18 by a general strike. By May 9, the governor was compelled to declare a state of emergency. Nevertheless, the strike and violence continued until July 7, when the Labour Relations Bill was allowed to lapse without being enacted. To bring an end to the disorder, the government agreed to consult with union representatives before introducing similar bills. These disturbances exacerbated tension and animosity between the two major ethnic communities and made a reconciliation between Jagan and Burnham an impossibility.

Jagan's term had not yet ended when another round of labor unrest rocked the colony. The pro-PPP GIWU, which had become an umbrella group of all labor organizations, called on sugar workers to strike in January 1964. To dramatize their case, Jagan led a march by sugar workers from the interior to Georgetown. This demonstration ignited outbursts of violence that soon escalated beyond the control of the authorities. On May 22, the governor finally declared another state of emergency. The situation continued to worsen, and in June the governor assumed full powers, rushed in British troops to restore order, and proclaimed a moratorium on all political activity. By the end of the turmoil, 160 people were dead and more than 1,000 homes had been destroyed.

In an effort to quell the turmoil, the country's political parties asked the British government to modify the constitution to provide for more proportional representation. The colonial secretary proposed a fifty-three member unicameral legislature. Despite opposition from the ruling PPP, all reforms were implemented and new elections set for October 1964.

As Jagan feared, the PPP lost the general elections of 1964. The politics of apan jhaat, Hintçe for "vote for your own kind", were becoming entrenched in Guyana. The PPP won 46 percent of the vote and twenty-four seats, which made it the largest single party but short of an overall majority. However, the PNC, which won 40 percent of the vote and twenty-two seats, and the UF, which won 11 percent of the vote and seven seats, formed a coalition. The socialist PNC and unabashedly capitalist UF had joined forces to keep the PPP out of office for another term. Jagan called the election fraudulent and refused to resign as prime minister. The constitution was amended to allow the governor to remove Jagan from office. Burnham became prime minister on December 14, 1964.

Independence and the Burnham era

Burnham in power

In the first year under Forbes Burnham, conditions in the colony began to stabilize. The new coalition administration broke diplomatic ties with Küba and implemented policies that favored local investors and foreign industry. The colony applied the renewed flow of Western aid to further development of its infrastructure. A constitutional conference was held in Londra; the conference set May 26, 1966 as the date for the colony's independence. By the time independence was achieved, the country was enjoying economic growth and relative domestic peace.

The newly independent Guyana at first sought to improve relations with its neighbors. For instance, in December 1965 the country had become a charter member of the Karayip Serbest Ticaret Derneği (Carifta). Relations with Venezuela were not so placid, however. In 1962 Venezuela had announced that it was rejecting the 1899 boundary and would renew its claim to all of Guyana west of the Essequibo Nehri. In 1966, Venezuela seized the Guyanese half of Ankoko Island, içinde Cuyuni Nehri, and two years later claimed a strip of sea along Guyana's western coast.

Another challenge to the newly independent government came at the beginning of January 1969, with the Rupununi Uprising. İçinde Rupununi region in southwest Guyana, along the Venezuelan border, white settlers and Kızılderililer merkezi hükümete isyan etti. Several Guyanese policemen in the area were killed, and spokesmen for the rebels declared the area independent and asked for Venezuelan aid. Troops arrived from Georgetown within days, and the rebellion was quickly put down. Although the rebellion was not a large affair, it exposed underlying tensions in the new state and the Amerindians' marginalized role in the country's political and social life.

The cooperative republic

1968 seçimleri izin verdi PNC to rule without the UF. The PNC won thirty seats, the PPP nineteen seats, and the UF four seats. However, many observers claimed the elections were marred by manipulation and coercion by the PNC. The PPP and UF were part of Guyana's political landscape but were ignored as Burnham began to convert the machinery of state into an instrument of the PNC.

After the 1968 elections, Burnham's policies became more leftist as he announced he would lead Guyana to socialism. He consolidated his dominance of domestic policies through Seçimde Hile Yapmak, manipulation of the balloting process, and politicalization of the civil service. A few Indo-Guyanese were co-opted into the PNC, but the ruling party was unquestionably the embodiment of the Afro-Guyanese political will. Although the Afro-Guyanese middle class was uneasy with Burnham's leftist leanings, the PNC remained a shield against Indo-Guyanese dominance. The support of the Afro-Guyanese community allowed the PNC to bring the economy under control and to begin organizing the country into kooperatifler.

On February 23, 1970, Guyana declared itself a "cooperative republic" and cut all ties to the İngiliz monarşisi. Genel Vali was replaced as head of state by a ceremonial Devlet Başkanı. Relations with Cuba were improved, and Guyana became a force in the Hizasız Hareket. In August 1972, Burnham hosted the Conference of Foreign Ministers of Nonaligned Countries Georgetown'da. He used this opportunity to address the evils of emperyalizm and the need to support African liberation movements Güney Afrika'da. Burnham also let Cuban troops use Guyana as a transit point on their way to the savaş içinde Angola 1970'lerin ortalarında.

In the early 1970s, electoral fraud became blatant in Guyana. PNC victories always included overseas voters, who consistently and overwhelmingly voted for the ruling party. The police and military intimidated the Indo-Guyanese. The army was accused of tampering with ballot boxes.

Considered a low point in the democratic process, the 1973 seçimleri were followed by an amendment to the constitution that abolished legal appeals to the Özel meclis Londrada. After consolidating power on the legal and electoral fronts, Burnham turned to mobilizing the masses for what was to be Guyana's cultural revolution. A program of Ulusal hizmet was introduced that placed an emphasis on self-reliance, loosely defined as Guyana's population feeding, clothing, and housing itself without outside help.

Devlet otoriterlik increased in 1974 when Burnham advanced the "paramountcy of the party". All organs of the state would be considered agencies of the ruling PNC and subject to its control. The state and the PNC became interchangeable; PNC objectives were now public policy.

Burnham's consolidation of power in Guyana was not total; opposition groups were tolerated within limits. For instance, in 1973 the Çalışan Halk İttifakı (WPA) was founded. Opposed to Burnham's authoritarianism, the WPA was a multi-ethnic combination of politicians and intellectuals that advocated racial harmony, free elections, and democratic socialism. Although the WPA did not become an official political party until 1979, it evolved as an alternative to Burnham's PNC and Jagan's PPP.

Jagan's political career continued to decline in the 1970s. Outmaneuvered on the parliamentary front, the PPP leader tried another tactic. In April 1975, the PPP ended its boykot of parliament with Jagan stating that the PPP's policy would change from noncooperation and civil resistance to critical support of the Burnham regime. Soon after, Jagan appeared on the same platform with Prime Minister Burnham at the celebration of ten years of Guyanese independence, on May 26, 1976.

Despite Jagan's conciliatory move, Burnham had no intention of sharing powers and continued to secure his position. When overtures intended to bring about new elections and PPP participation in the government were brushed aside, the largely Indo-Guyanese sugar work force went on a bitter vuruş. The strike was broken, and sugar production declined steeply from 1976 to 1977. The PNC postponed the 1978 elections, opting instead for a referendum to be held in July 1978, proposing to keep the incumbent assembly in power.

The July 1978 national referendum was poorly received. Although the PNC government proudly proclaimed that 71 percent of eligible voters participated and that 97 percent approved the referendum, other estimates put turnout at 10 to 14 percent. The low turnout was caused in large part by a boycott led by the PPP, WPA, and other opposition forces.

The Jonestown massacre

Burnham's control over Guyana began to weaken when the Jonestown massacre brought unwanted international attention. 1970 lerde, Jim Jones lideri People's Temple of Christ, moved more than 1,000 of his followers from San Francisco oluşturmak üzere Jonestown, bir ütopik agricultural community near Port Kaituma in western Guyana. The People's Temple of Christ was regarded by members of the Guyanese government as a model agricultural community that shared its vision of settling the hinterland and its view of cooperative socialism. The fact that the People's Temple was well equipped with openly flaunted weapons hinted that the community had the approval of members of the PNC's inner circle. Complaints of abuse by leaders of the cult prompted United States congressman Leo Ryan to fly to Guyana to investigate. The San Francisco-area representative was shot and killed by members of the People's Temple as he was boarding an airplane in Port Kaituma to return to Georgetown. Fearing further publicity, Jones and more than 900 of his followers died in a massive communal murder and suicide. The November 1978 Jonestown massacre suddenly put the Burnham government under intense foreign scrutiny, especially from the United States. Investigations into the massacre led to allegations that the Guyanese government had links to the fanatical cult.

Burnham's last years

Although the bloody memory of Jonestown faded, Guyanese politics experienced a violent year in 1979. Some of this violence was directed against the WPA, which had emerged as a vocal critic of the state and of Burnham in particular. One of the party's leaders, Walter Rodney, and several professors at the Guyana Üniversitesi were arrested on kundakçılık ücretleri. The professors were soon released, and Rodney was granted bail. WPA leaders then organized the alliance into Guyana's most vocal opposition party.

As 1979 wore on, the level of violence continued to escalate. In October Minister of Education Vincent Teekah was mysteriously shot to death. The following year, Rodney was killed by a car bomb. The PNC government quickly accused Rodney of being a terrorist who had died at the hands of his own bomb and charged his brother Donald with being an accomplice. Later investigation implicated the Guyanese government, however. Rodney was a well-known leftist, and the circumstances of his death damaged Burnham's image with many leaders and intellectuals in less-developed countries who earlier had been willing to overlook the authoritarian nature of his government.

A new constitution was promulgated in 1980. The old ceremonial post of president was abolished, and the hükümetin başı olmak icra başkanı, chosen, as the former position of prime minister had been, by the majority party in the Ulusal Meclis. Burnham automatically became Guyana's first executive president and promised elections later in the year. In elections held on December 15, 1980, the PNC claimed 77 percent of the vote and forty-one seats of the popularly elected seats, plus the ten chosen by the regional councils. The PPP and UF won ten and two seats, respectively. The WPA refused to participate in an electoral contest it regarded as fraudulent. Opposition claims of electoral fraud were upheld by a team of international observers headed by Britain's Lord Avebury.

The economic crisis facing Guyana in the early 1980s deepened considerably, accompanied by the rapid deterioration of public services, infrastructure, and overall quality of life. Blackouts occurred almost daily, and water services were increasingly unsatisfactory. The litany of Guyana's decline included shortages of rice and sugar (both produced in the country), cooking oil, and kerosene. While the formal economy sank, the black market economy in Guyana thrived.

In the midst of this turbulent period, Burnham underwent surgery for a throat ailment. On August 6, 1985, while in the care of Cuban doctors, Guyana's first and only leader since independence unexpectedly died.

Hoyte to present

Despite concerns that the country was about to fall into a period of political instability, the transfer of power went smoothly. Başkan Vekili Desmond Hoyte became the new executive president and leader of the PNC. His initial tasks were threefold: to secure authority within the PNC and national government, to take the PNC through the December 1985 elections, and to revitalize the stagnant economy.

Hoyte's first two goals were easily accomplished. The new leader took advantage of factionalism within the PNC to quietly consolidate his authority. The December 1985 elections gave the PNC 79 percent of the vote and forty-two of the fifty-three directly elected seats. Eight of the remaining eleven seats went to the PPP, two went to the UF, and one to the WPA. Charging fraud, the opposition boycotted the December 1986 municipal elections. With no opponents, the PNC won all ninety-one seats in local government.

Revitalizing the economy proved more difficult. As a first step, Hoyte gradually moved to embrace the private sector, recognizing that state control of the economy had failed. Hoyte's administration lifted all curbs on foreign activity and ownership in 1988.

Although the Hoyte government did not completely abandon the authoritarianism of the Burnham regime, it did make certain political reforms. Hoyte abolished overseas voting and the provisions for widespread proxy and postal voting. Independent newspapers were given greater freedom, and political harassment abated considerably.

Former U.S. President Jimmy Carter visited Guyana to lobby for the resumption of free elections, and on October 5, 1992, a new National Assembly and regional councils were elected in the first Guyanese election since 1964 to be internationally recognized as free and fair. Cheddi Jagan of the PPP was elected and sworn in as President on October 9, 1992, reversing the monopoly Afro-Guyanese traditionally had over Guyanese politics. The poll was marred by violence however. Yeni Uluslararası Para Fonu Structural Adjustment programme was introduced which led to an increase in the GDP whilst also eroding real incomes and hitting the middle-classes hard.

When President Jagan died of a heart attack in March 1997, Prime Minister Samuel Hinds replaced him in accordance with constitutional provisions, with his widow Janet Jagan as Prime Minister. She was then elected President on fifteenth December 1997 for the PPP. Desmond Hoyte's PNC contested the results however, resulting in strikes, riots and one death before a Caricom mediating committee was brought in. Janet Jagan's PPP government was sworn in on 24 December having agreed to a constitutional review and to hold elections within three years, though Hoyte refused to recognise her government.

Jagan resigned in August 1999 due to ill health and was succeeded by Finance Minister Bharrat Jagdeo, who had been named Prime Minister a day earlier. National elections were held on March 19, 2001, three months later than planned as the election committees said they were unprepared. Fears that the violence that marred the previous election led to monitoring by foreign bodies, including Jimmy Carter. In March incumbent President Jagdeo won the election with a voter turnout of over 90%.

Meanwhile, tensions with Suriname were seriously strained by a dispute over their shared maritime border after Guyana had allowed oil-prospectors license to explore the areas.

In December 2002, Hoyte died, with Robert Corbin replacing him as leader of the PNC. He agreed to engage in 'constructive engagement ' with Jagdeo and the PPP.

Severe flooding following torrential rainfall wreaked havoc in Guyana beginning in January 2005. The downpour, which lasted about six weeks, inundated the coastal belt, caused the deaths of 34 people, and destroyed large parts of the rice and sugarcane crops. The UN Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean estimated in March that the country would need $415 million for recovery and rehabilitation. About 275,000 people—37% of the population—were affected in some way by the floods. 2013 yılında Hope Canal was completed to address the flooding.[7]

In May 2008, President Bharrat Jagdeo was a signatory to The UNASUR Kurucu Antlaşması of Güney Amerika Ulusları Birliği. Guyana has ratified the treaty.

Ayrıca bakınız

- Amerika'nın İngiliz kolonizasyonu

- Amerika'nın Fransız kolonizasyonu

- Amerika tarihi

- Britanya Batı Hint Adaları Tarihi

- Güney Amerika tarihi

- Karayipler Tarihi

- Politics of Guyana

- List of Governors of British Guiana

- Guyana Genel Valileri Listesi

- Guyana Başkanları Listesi

- Guyana Başbakanları Listesi

- Amerika'nın İspanyol kolonizasyonu

daha fazla okuma

- Daly, Vere T. (1974). The Making of Guyana. Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-333-14482-4. Alındı 2011-01-07.CS1 bakimi: ref = harv (bağlantı)

- Daly, Vere T. (1975). A Short History of The Guyanese People. Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-333-18304-5. Alındı 2011-01-07.CS1 bakimi: ref = harv (bağlantı)

- Hope, Kempe Ronald (1985). Guyana: Politics and Development in an Emergent Socialist State. Oakville, Ont: Mosaic Press. ISBN 0-88962-302-3. Alındı 2011-01-07.CS1 bakimi: ref = harv (bağlantı)

- Révauger, Cécile (Ekim 2008). The Abolition of Slavery – The British Debate 1787–1840. Presse Universitaire de France. ISBN 978-2-13-057110-0. Alındı 2011-01-07.CS1 bakimi: ref = harv (bağlantı)Spinner, Thomas J. (1984). A Political and Social History of Guyana, 1945–1983. Boulder, Colo: Westview Press. ISBN 0-86531-852-2. Alındı 2011-01-07.CS1 bakimi: ref = harv (bağlantı)

- Sued-Badillo, Jalil, ed. (2003). General History of the Caribbean: Volume I: Autochthonous Societies. Paris: UNESCO. ISBN 0-333-72453-4.

- Henry, Paget; Stone, Carl (1983). The Newer Caribbean: Decolonization, Democracy, and Development. Volume 4 of Inter-American politics series. Philadelphia: Institute for the Study of Human Issues. ISBN 0-89727-049-5. Alındı 2011-01-07.CS1 bakimi: ref = harv (bağlantı)

- This article includes information from the public domain Library of Congress Guyana country study.

Referanslar

- ^ Kreeke, Frank van de (2013). "Essequebo en Demerary, 1741-1781: beginfase van de Britse overname" (PDF). Leiden University Master Thesis. Alındı 2015-03-23.

- ^ https://legal.un.org/riaa/cases/vol_XXVIII/331-340.pdf

- ^ a b Révauger 2008, s. 105–106.

- ^ "Former Deputy Prime Minister Brindley Benn dies at 86 ", Guyana Chronicle, December 12, 2009

- ^ Hirsch, Fred, The Labour Movement: Penetration Point for U.S. Intelligence and Transnationals, Spokesman Books, 1977

- ^ Brereton, Bridget, Karayiplerin Genel Tarihi: Yirminci Yüzyılda Karayipler, [1], UNESCO 2004

- ^ "Good Hope Canal releasing water from EDWC". Stabroek Haberleri. 2016-12-29. Alındı 2020-12-07.